- Home

- Julie Hodgson

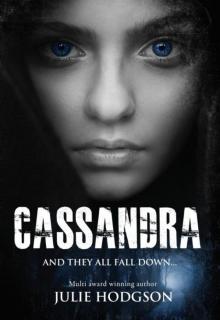

Cassandra: And they all fall down

Cassandra: And they all fall down Read online

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic or electronic process, or in the form of phonographic recording, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or otherwise be copied for public or private use, other than ‘fair use,’ as brief quotations embodied in articles or reviews, without prior written permission of the publisher or author.

www.juliehodgson.com

All rights reserved © Julie Hodgson 2017

ISBN 978-91-88045-27-0

Dedicated:

To all those who are made to feel different, to all those that struggle…

We ARE all the same…Only our attitude makes us unique.

You know who you are…... JH.

Contents

PREFACE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

PROLOGUE

Preface

The blood should have made her nauseous, should have twisted her stomach into a knot of rats’ tails. There was so much of it. It should have sent her into shock, curdled her insides. But she just stood there watching it drool off her fingers and beyond, where the remains of the bodies, now unrecognizable, were a blur of red amongst the forest greens and browns, delicately illuminated by the moon that had never been so complete and bright. The only delicate thing about the scene before her was this lighting and it would mask the horror until the morning. But her eyes were receptive to every last animal tear and slash of flesh, every discarded, skinned limb, the eyeballs and tongue, the feet and hands, the trail of intestines splayed out on the dusty woodland clearing as if a wild beast had torn at them with razor-sharp teeth. And the smell; it should have triggered her gag reflex and doubled her over, but it moved in and out of her – a swirling concoction of feces and puke – and powered her lungs as if she needed it to survive. The halting of their heartbeats had rung in her ears with every bit as much clarity as the powerful life force that had been pounding through them, and now all she could hear was the absence of sound apart from the leaves gently rustling in the midnight breeze. She took a deep breath, closed her eyes and sank into and almost hypnagogic peace.

She had done this. She had actually done this, and now everything made sense to her. The way she experienced the world, her past, the feelings she had tried to deal with for so much of her life, which would rise up inside of her and try to force their way out of her flesh by any means possible, the nightmares. Pure-red gore that had terrorized her for so much of her life – the maddening itch on the backs of her hands, the way her mother would occasionally flinch when she turned to hug her. It all made perfect sense now, and in this moment of calm, it felt as if she had found a home in this forest, in this blood, for the first time in her entire life. But it also made no sense at all. She was now a murderer and a savage one at that.

Chapter One

She had hurt a child. That’s why she had started taking the tablets in the first place. They said it was ADD. Perhaps it was. She was a child then, so it wasn’t as monstrous as it sounded, but it was the trigger that fired her into the system of health and social monitoring and daily meds that, a month before her sixteenth birthday, the doctor was about to tell her she no longer needed.

She remembered the incident as if it were yesterday as if it were still happening somewhere inside of her. Braydon Taylor. He was an ugly child, although no one would have said it to him. His parents probably loved him as best they could, and maybe they didn’t even notice his ugliness because it came from a dark place buried deep within his soul. If he hadn’t been such a little monster, he probably would have been quite cute-looking. All of his features were in the right place – but this shadowy something rose up and made his eyes dark and cunning, his nose wrinkled, and his mouth always in a state of flux between a sadistic smile and spewing forth the verbal filth inside of him that regularly made other kids cry. Maybe his parents were like that? Who knows.

At six years, old, Cassandra was beginning to discover how faces could be twisted and deformed by the beasts that lived inside. Equally, people became more and more attractive as their goodness spilled into the world. Her mommy and daddy, for example, were the most beautiful people she would ever see, but even at six years old she wondered what people saw when they looked into her eyes. She had always been told she was a beautiful princess and people liked to smile around her, so she had no reason to question it, but still the uncertainty came.

Braydon Taylor’s ugliness was flung in the general direction of whoever got in his way. It was indiscriminate, but with the exception of little boy, Jakey, he too “got in his way” more than most, which was ironic because he was tiny and terrified and always tried to hide from Braydon, but he always ended up being relieved of his lunch money or on the business end of a kick, punch, or glob of spit. No one could ever accuse Jakey of being ugly; he was the exact opposite of Braydon – angelic, blonde-haired, blue-eyed, freckled, with a smile that melted the teachers’ hearts. But teachers aren’t always around to protect, no matter how hard they try.

It was summer. This is important to the memory because it was only in the summertime that kids from the elementary school took excursions out to the local farms. This particular day was a cauldron of fire, and the heat had prickled under the skin of all the children, so there had already been tears and tantrums by the time they got the bus out to the farm. The teacher, Miss Furle, a slight but imposing figure with big 80’s style hair and a voice that carried from one end of the school to the other, had talked about canceling the field trip, but the principal had been persistent. Of course, Cassandra knew none of this. She just knew that she was so hot on the bus that her skin had gone sticky and her head was beginning to throb. The backs of her hands also itched as they so often did. She also knew that Braydon Taylor, whether caused by the sun or not, was being a bigger pain in the ass than normal and Jakey was the focus of his abuse. He had managed to cajole the other boys, who were all terrified of him, to sing the ‘Jakey Song,' which mostly told Jakey how much he stank and how much everyone hated him. He had taken his lunch and the money his mom slipped into his pocket in case there was anything to buy at the farmhouse. Finally, humiliation heaped on humiliation, he pulled Jakey’s shorts and underpants down. Now the whole class had seen what he kept in there and pretty much all of them found it hilarious. Jakey was still bright red and teary when they reached the farm.

It was hot. It was too hot. It was the kind of heat that forced animals either onto their bellies and under the shade, or it was a red-hot poker, jabbing them up onto their hind legs, forcing howls and screams into the air. Thankfully, all the animals on the farm just couldn’t be bothered to let the heat do anything other than soothe them to sleep, and most of the children also allowed the heat to subdue them. As they walked around the diverse fenced areas and were told all about the different animals, they were yawning, and there were occasional tears. They were six years old, and it was too hot to do anything. Even Braydon was behaving himself, and it was only when they assembled for lunch in the open picnic area that Miss Furle noticed a very serious problem. They had lost Jakey.

The adults spent the next half hour looking for the boy while the children remained in the picnic area with Miss Furle, eating their lunches to a mumbled accompaniment of worried giggles

. The biggest giggler of all was Braydon, who was bubbling over with glee, and as Cassandra looked across to that ugly, nasty face, the heat rose in her and forced her up onto her hind legs. She was sitting with Sally, but she couldn’t keep her eyes off him, sitting up on the fence, swinging his legs in that carefree way while Jakey was God only knew where. Her hands were itching so fiercely now that she had almost rubbed a hole in them with the scratching. And then she couldn’t contain the fire any longer. She leapt back from her chair, sending it crashing behind her, and ran at Braydon with her fists fixed in front of her. She knocked him backwards, off the fence, and landed on top of him, knocking that smile off his stupid ugly face.

“He’s in the chicken house!” he shouted. “He’s in the chicken house!”

But Cassandra didn’t let him up straight away. She couldn’t. There was something inside of her, taking control of her, forcing her to act on poor Jakey’s behalf, who would be terrified in the dark, shitty chicken house.

“He’s in the chicken house!” He was sobbing now, but she couldn’t stop herself, and then, as quickly as this thing inside of her had risen, it started to descend, and she felt a wave of calm. Miss Furle was rushing over to them now, but Cassandra had only one thing on her mind. She had to get to the chicken house and free Jakey. She finally jumped off Braydon and sprinted across the field to where she had remembered seeing the fat, lazy, brown and orange birds, barely willing to walk from one end of their coop to the other in the heat. She could hear the crying before she even got there. She reached her tiny fingers up to unlock the gate, and the chickens seemed uninterested in her as she entered their world. She then skipped over to the tiny square door, which was also locked, and flipped the catch. Little Jakey came tumbling out, his face red and drenched from the tears, covered in brown chicken mess, straw, and red scratches either from himself or the chickens. Jakey had suffered tremendously at the vicious hands of Braydon Taylor.

“It’s okay, Jakey,” she told him in her sweet, little voice, now completely calm and settled again, and she slipped her hand into his and led him out into the grassy walkway. He was still sobbing as they walked, but by the time they had returned to the picnic area he seemed a little calmer and his little hand felt less shaky, but he would always be traumatized by small spaces from that day on and it would take him years to shake the nightmares.

“He’s okay!” Cassandra shouted as she led him towards the tables, but there were no longer children around. She could count five adults, and they were standing in a circle around by the back of the fence where Braydon had been sitting. Eventually, Miss Furle caught sight of the two of them and ran over. She took Jakey’s hand and scurried away with him without saying a word, but her darkened eyes didn’t leave Cassandra’s.

“Miss?” Cassandra said, but the teacher had spun away in the direction of the bus, leaving her alone among the half-eaten lunches and the earthy reek of animals. “Miss,” she tried again and then slowly began to walk over to the other adults, a few other teachers and farm workers. When she got a little closer, she was able to see what they were looking at, and the sight of it made her tummy flip. She had never really seen blood before, and now there was so much of it that it looked unreal. Braydon was asleep in it. It was his blood. It was oozing out of him, like thick red treacle on a carpet of green.

“What …?” she tried, but the words were stuck in her throat.

All the adults turned to look at her with grave, incredulous faces.

“What happened to him?” she asked in her tiny voice, absorbing the way his arm and one of his legs were bending at unnatural angles, and how there was a dotted circle on his forehead, like teeth marks. “Who did this to him?”

No one said anything for a moment and then an angry voice said, “You did.”

She was then whisked away in much the same way Miss Furle had removed Jakey. Only, rather than being taken back to the bus, she was dragged across to the farm office to await her parents. As she waited, she heard the sirens, but then her memory skips her to the doctor’s office. There’s something wrong with her, that’s what they’re telling her parents as she listens, perched on a chair too high for her feet to reach the floor. The nightmares she has been having, the itching and the scratching of the backs of her hands, the way she put Braydon in the hospital for two months; she has some kind of imbalance that’s causing all these things and can be managed with medication. If there was ever police involvement, she never knew about it. She not only changed schools, but the family moved away from any memory of the incident, to Garden City, and the only time the incident was ever referred to again was at her reviews at the doctor’s office, which was exactly where she was now, one month before her sixteenth birthday.

Dr. Somner had definitely aged over the years that Cassandra had been going to see him, which was all her life, but he had always been old to her; if anything, he was even older when she was tiny. All adults are a hundred years old when we’re looking up at them from waist height, but Dr. Somner was probably born with those wrinkled hands and liver spots. When she was little she was fascinated by him; jagged, metallic hairs sprouted from his nostrils and burst out of his ears like weeds in a garden that would never bear fruit or flower, but the white hair on his head was far more fun and bouncy if hair could be fun. It was cotton candy and clouds, and it gave him a fanciful appearance that mesmerized her. Now, through teenage eyes, he was just old and boring, and so were these dreary appointments that Cassandra had to attend every six months; everything he said was old and boring.

“You’re growing into a fine young woman,” he said, then turned to Cassandra’s mom. “And you seem to be getting younger by the day, Ellen. You must be mistaken for sisters all the time rather than mother and daughter.”

Vomit! Cassandra wasn’t sure if it was flirting or just the kind of thing doctors said. Yes, they looked a little alike with the long blonde hair that both wore long and same cornflower blue eyes, but sisters? He was obviously now so old that his eyesight was beginning to fail him.

Although she mocked him repeatedly in her mind, she had heard the stories about the way he had done everything in his power to make sure her mother had recovered from cervical cancer before Cassandra was born and then orchestrate the magic of her birth through IVF after two miserable, failed attempts. He was partly, if not wholly, responsible for the fact that Cassandra and her mother were able to walk on this earth, open the door to his office, come in, and take a seat, but it was hard to hold this in her mind while he was droning on. Rather than gratitude, Cassandra let the sound of his voice – in fact, everything about the office, down to the weird, new-car smell – frustrate her. Her birthday was only a month away, and she had a hundred things to do. She only got one shot at being sixteen, and she was determined to get it right. She was officially only having a small family get-together to celebrate, but that was because she shared a birthday with Abby, the richest girl in school, and as popular as Cassandra was, Abby’s party would be the sweet sixteen to end all sweet sixteens. It was the year of the sweet sixteen. Cassandra had already been to three, and they were only partway through the semester. It was looking to be the best year of her life so far, and she had gotten over being bummed that she had to share it with Abby. It happened every single year, and she had learned to simply hold her own party within the carnival that was always Abby’s. Her family could never afford to lavish such a celebration on her, so it actually worked out for the best. This year, she had a fleeting few days of wishing there was some way of having her own sweet sixteen, maybe on a different day to Abby’s, but she knew hers would be overshadowed. And besides, her classmates knew how it worked and would bring gifts for her to the party. Even Abby knew how it worked, although she was less happy about sharing the spotlight than Cassandra, but she had probably gotten used to it over the years, too. But there was so much still to do. She hadn’t even finalized her outfit; what was the perfect outfit for a party out in the woods? Greens? Browns? Or should she just i

gnore the setting and pick a favorite? Was there still time to twist her dad’s arm and his ATM card into buying her a new outfit. And then she had the track meet. This was a week before the party, and there was so much riding on it. The whole school would be looking to her to smash the 100 meters. Although college was years ahead of her, the scouts liked to catch their athletes young. All of this spun round and round in her head, and Cassandra only realized she had lost herself in thought when she saw that Dr. Somner and her mother were both looking at her, waiting for her to answer whatever one of them had just said to her.

“… I mean,” Dr. Somner continued, clarifying the question in case she hadn’t understood. “Do you feel ready to try living without the medication?”

Without the medication? Where had this come from? She could usually just coast her way through these appointments, nodding and smiling in all the right places. She sometimes had more to say, if she had been having the nightmares, or if her hands had been itching, but Dr. Somner never had answers for her anyway, so she learned that keeping quiet got her out and back to her friends or the track a lot quicker.

“Er … sorry, without the medication?”

“The doctor seems confident that you should have a break from the medication.”

Cassandra turned to her mother, but couldn’t read the expression. Maybe there was nothing there to read. She didn’t look to be objecting or supporting the idea, rather bringing it to Cassandra’s attention while claiming absolutely no responsibility for it. The little smile she always wore was there, but this wasn’t because she was happy. It was the smile of an incredibly beautiful woman who had suffered, through cancer and infertility but was determined not to quit. She had pasted it on her face, this slim, sometimes barely visible smile, when she was diagnosed. When her hair was falling out in clumps, and she was throwing up after each chemo session; she had held it there when she woke from surgery and was too frail to walk, and it had remained every month that followed.When they had tried for a baby and her body repeatedly showed her that they had failed. Eventually, the smile, as faint and distant as it sometimes was, needed absolutely nothing from her to exist and had taken a life of its own. So it was there whether she was happy or sad, whether she feared for her daughter coming off her meds or not, and the world could see what a brave woman she was. It was usurped by the fullest, most radiant smile and a week of laughter when she discovered that she was actually pregnant. But she was forced to pull that brave smile out again for a pregnancy that hospitalized her twice, such was the pain and sickness that she experienced, and labor that nearly killed her.

Cassandra: And they all fall down

Cassandra: And they all fall down